Your Constitutional Right To Counsel: The Prosecution Can’t Take Your Money

Luis v United States

136 S.Ct. 1083

The United States Supreme Court

Decided on: March 30, 2016

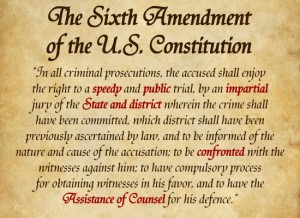

Issue: Whether the pretrial restraint of a criminal defendant’s legitimate, untainted assets, those not traceable to a criminal offense, needed to retain counsel of choice, violates the Sixth Amendment.

Holding:? The United States Supreme Court held that the pretrial restraint of legitimate, untainted assets needed to retain counsel of choice violates the Sixth Amendment.

The Sixth Amendment right to counsel grants a defendant a fair opportunity to secure counsel of his own choice, Powell v Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 53 that he can afford to hire, Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered v United States, 491 U.S. 617, 624.

While the Government does not deny Luiss fundamental right to be represented by a qualified attorney whom she chooses and can afford to hire, it would nonetheless undermine the value of that right by taking from Luis the ability to use funds she needs to pay for her chosen attorney.

Facts: A federal grand jury charged the petitioner, Sila Luis, with paying kickbacks, conspiring to commit fraud, and engaging in other crimes all related to health care, 1349; 371; 42 U.S.C. 1320a 7b(b)(2)(A). The Government claimed that Luis had fraudulently obtained close to $45 million, almost all of which she had already spent. Believing it would convict Luis of the crimes charged, and hoping to preserve the $ 2 million remaining in Luiss possession for payment of restitution and other criminal penalties, the Government sought a pretrial order prohibiting Luis from dissipating her assets, 18 U.S.C 1345(a)(2). And the District Court ultimately issued an order prohibiting her from dissipating or otherwise disposing of assets real or personal up to the equivalent value of the proceeds of the Federal health care fraud.

Facts: A federal grand jury charged the petitioner, Sila Luis, with paying kickbacks, conspiring to commit fraud, and engaging in other crimes all related to health care, 1349; 371; 42 U.S.C. 1320a 7b(b)(2)(A). The Government claimed that Luis had fraudulently obtained close to $45 million, almost all of which she had already spent. Believing it would convict Luis of the crimes charged, and hoping to preserve the $ 2 million remaining in Luiss possession for payment of restitution and other criminal penalties, the Government sought a pretrial order prohibiting Luis from dissipating her assets, 18 U.S.C 1345(a)(2). And the District Court ultimately issued an order prohibiting her from dissipating or otherwise disposing of assets real or personal up to the equivalent value of the proceeds of the Federal health care fraud.

The Government and Luis agree that this court order will prevent Luis from using her own untainted funds, i.e., funds not connected with the crime, to hire counsel to defend her in her criminal case. See App. 161. Although the District Court recognized that the order might prevent Luis from obtaining counsel of her choice, it held that there is no Sixth Amendment right to use untainted substitute assets to hire counsel. 966 F. Supp. 2d 1321, 1334 ( SD Fla. 2013).

The Eleventh Circuit upheld the District Court and the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. The question presented is whether the pretrial restraint of a criminal defendant’s legitimate, untainted assets, those not traceable to a criminal offense, needed to retain counsel of choice violates the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. The Court held that the pretrial restraint of legitimate, untainted assets needed to retain counsel of choice violates the Sixth Amendment.

Legal Analysis: The Court held that no one doubts the fundamental character of a criminal defendants Sixth Amendment right to the assistance of counsel. In Gideon v Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), the Court explained:

The right to be heard would be, in many cases, of little avail if it did not comprehend the right to be heard by counsel. Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of the law. If charged with a crime, he is incapable, generally, of determining for himself whether the indictment is good or bad. He is unfamiliar with the rules of evidence. Left without the aid of counsel he may be put on trial without a proper charge, and convicted upon incompetent evidence, or evidence irrelevant to his issue or otherwise inadmissible. He lacks both the skill and knowledge adequately to prepare his defense, even though he have a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence, Id., at 344-345 quoting Powell v Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 68-69 (1932).

The Court held that a federal statute provides that a court may freeze before trial certain assets belonging to a criminal defendant accused of violations of federal health care of banking laws, 18 U.S.C. 1345. Those assets include: (1) property obtained as a result of the crime, (2) property traceable to the crime, and (3) other property of equivalent value, 1345(a)(2). In this case, the Government has obtained a court order that freezes assets belonging to the third category of property, namely, property that is untainted by the crime, and that belongs fully to the defendant. That order, the defendant says, prevents her from paying for her lawyer. She claims that insofar as it does so, it violates her Sixth Amendment right to have the assistance of counsel in her defense; the Court agrees.

It is consequently not surprising: first, that this Courts opinions often refer to the right to counsel as fundamental, id., at 68; see Grosjean v American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233, 243-244 (1936; Johnson v Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 462-463 (1938); second, that commentators describe the right as a great engine by which an innocent man can make the truth of his innocence visible, Amar, Sixth Amendment First Principles, 84 GEO. L. J. 641, 643 (1996); Herring v New York, 422 U.S. 853, 862 (1975); third, that we have understood the right to require that the Government provide counsel for an indigent defendant accused of all but the least serious crimes, see Gideon, supra, at 344; and fourth, that the United States Supreme Court has considered the wrongful deprivation of the right to counsel a structural error that so affects the framework within which the trial proceeds that courts may not even ask whether the error harmed the defendant, United States v Gonzalez-Lopez, 548 U.S. 140, 148(2006).

Given the necessarily close working relationship between lawyer and client, the need for confidence, and the critical importance of trust, neither is it surprising that the Court has held that the Sixth Amendment grants defendant a fair opportunity to secure counsel of his own choice, Powell, supra, at 53; see Gonzalez-Lopez, supra, at 150. This fair opportunity for the defendant to secure counsel of choice has limits. A defendant has no right, for example, to an attorney who is not a member of the bar, or who has a conflict of interest due to a relationship with an opposing party. See Wheat v. United States, 486 U. S. 153, 159 (1988). And an indigent defendant, while entitled to adequate representation, has no right to have the Government pay for his preferred representational choice. See Caplin & Drysdale, 491 U. S., at 624.

The Supreme Court held that they nonetheless emphasize that the constitutional right at issue here is fundamental: The Sixth Amendment guarantees a defendant the right to be represented by an otherwise qualified attorney whom that defendant can afford to hire. Ibid. The Government cannot, and does not, deny Luiss right to be represented by a qualified attorney whom she chooses and can afford. But the Government would undermine the value of that right by taking from Luis the ability to use the funds she needs to pay for her chosen attorney.

The Supreme Court held that they nonetheless emphasize that the constitutional right at issue here is fundamental: The Sixth Amendment guarantees a defendant the right to be represented by an otherwise qualified attorney whom that defendant can afford to hire. Ibid. The Government cannot, and does not, deny Luiss right to be represented by a qualified attorney whom she chooses and can afford. But the Government would undermine the value of that right by taking from Luis the ability to use the funds she needs to pay for her chosen attorney.

The Government points out that, while freezing the funds may have this consequence, there are important interests on the other side of the legal equation: It wishes to guarantee that those funds will be available later to help pay for statutory penalties (including forfeiture of untainted assets) and restitution, should it secure convictions. And it points to two cases from this Court, Caplin & Drysdale, supra, at 619, and Monsanto, 491 U. S., at 615, which, in the Governments view, hold that the Sixth Amendment does not pose an obstacle to its doing so here. In the Courts view, however, the nature of the assets at issue here differs from the assets at issue in those earlier cases. And that distinction makes a difference.

The relevant difference consists of the fact that the property here is untainted; i.e., it belongs to the defendant, pure and simple. In this respect it differs from a robbers loot, a drug sellers cocaine, a burglars tools, or other property associated with the planning, implementing, or concealing of a crime. The Government may well be able to freeze, perhaps to seize, assets of the latter, tainted kind before trial. As a matter of property law the defendants ownership interest is imperfect. The robbers loot belongs to the victim, not to the defendant. See Telegraph Co. v. Davenport, 97 U. S. 369, 372 (1878) The property at issue here, however, is not loot, contraband, or otherwise tainted. It belongs to the defendant. That fact undermines the Governments reliance upon precedent, for both Caplin & Drysdale and Monsanto relied critically upon the fact that the property at issue was tainted, and that title to the property therefore had passed from the defendant to the Government before the court issued its order freezing (or otherwise disposing of) the assets.

In Caplin & Drysdale, the Court considered a post- conviction forfeiture that took from a convicted defendant funds he would have used to pay his lawyer. The Court held that the forfeiture was constitutional. In doing so, however, it emphasized that the forfeiture statute at issue provided that all right, title and interest in property constituting or derived from any proceeds obtained from the crime vests in the United States upon the commission of the act giving rise to the forfeiture. 491 U. S., at 625, n. 4 (quoting 853(c)

In Monsanto, the Court considered a pretrial restraining order that prevented a not-yet-convicted defendant from using certain assets to pay for his lawyer. The defendant argued that, given this difference, Caplin & Drysdales conclusion should not apply. The Court noted, however, that the property at issue was forfeitable under the same statute that was at issue in Caplin & Drysdale. See Mon- santo, supra, at 614. And, as in Caplin & Drysdale, the application of that statute to Monsantos case concerned only the pretrial restraint of assets that were traceable to the crime, see 491 U. S., at 602?603; thus, the statute passed title to those funds at the time the crime was com? mitted (i.e., before the trial), see 853(c). The Court said that Caplin & Drysdale had already weighed the very interests at issue. Monsanto, supra, at 616. And it relied on its conclusion in Caplin & Drysdale to dispose of, and to reject, the defendants similar constitutional claims. Here, by contrast, the Government seeks to impose restrictions upon Luis untainted property without any showing of any equivalent governmental interest in that property.

The distinction that the Court has discussed is thus an important one, not a technicality. It is the difference between what is yours and what is mine. In Caplin & Drysdale and Monsanto, the Government wanted to impose restrictions upon or seize property that the Government had probable cause to believe was the proceeds of, or traceable to, a crime. The relevant statute said that the Government took title to those tainted assets as of the time of the crime. See 853(c). And the defendants in those cases consequently had to concede that the disputed property was in an important sense the Governments at the time the court imposed the restrictions. See Caplin & Drysdale, supra, at 619-620; Monsanto, supra, at 602-603. This is not to say that the Government owned the tainted property outright. Rather, it is to say that the Government even before trial had a substantial interest in the tainted property sufficient to justify the propertys pretrial restraint, Caplin & Drysdale supra at 627.

Here, by contrast, the Government seeks to impose restrictions upon Luiss untainted property without any showing of any equivalent governmental interest in that property.

Here, by contrast, the Government seeks to impose restrictions upon Luiss untainted property without any showing of any equivalent governmental interest in that property.

The Government here seeks a somewhat analogous order, i.e, an order that will preserve Luiss untainted assets so that they will be available to cover the costs of forfeiture and restitution if she is convicted, and if the court later determines that her tainted assets are insufficient or otherwise unavailable. The Government finds statutory authority for its request in language authorizing a court to enjoin a criminal defendant from, for example, disposing of innocent property of equivalent value of defendant to that of tainted property. 18 U.S.C. 1345(a)(2)(B)(i).

But Luis needs some portion of those same funds to pay for the lawyer of her choice. Thus, the legal conflict arises. And, the Court held in their view, insofar as innocent funds are needed to obtain counsel of choice; they believe that the Sixth Amendment prohibits the court order that the Government seeks. Moreover, the financial consequences of a criminal conviction are steep. Even beyond the forfeiture itself, criminal fines can be high, and restitution orders expensive. How are defendants whose innocent assets are frozen in cases like these supposed to pay for a lawyer?particularly if they lack tainted assets because they are innocent, a class of defendants whom the right to counsel certainly seek to protect, Powell, 287 U.S., at 69; Amar, 84 Geo. L.J., at 643. These defendants, rendered indigent, would fall back upon publicly paid counsel, including overworked and underpaid public defenders. As the department of Justice explains, only 27 percent of country-based public defender offices have sufficient attorneys to meet nationally recommended caseload standards. Dept. of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, D. Farole & L. Langton, Census of Public Defender Offices, 2007: County-based and Local Public Defender Offices, 2007, p. 10 (Sept. 2010). And as one amicus points out, many federal public defender organizations and lawyers appointed under the Criminal Justice Act serve numerous clients and have only limited resources, Brief for New York Council of Defense Lawyers 11. The upshot is a substantial risk that accepting the Governments views would-by increasing the government paid defender workload?render less effective the basic right the Sixth Amendment seeks to protect.

The United States Supreme Court adds that the constitutional line they have drawn should prove workable. That line distinguishes between a criminal defendants (1) tainted funds and (2) innocent funds needed to pay for counsel. The Court conceded, as Justice Kennedy points out, post, at 12-13, that money is fungible; and sometimes it will be difficult to say whether a particular bank account contains tainted or untainted funds. But the law has tracing rules that help courts implement the kind of distinction they require in this case. For the reasons stated, the United States Supreme Court conclude that the defendant in this case has a Sixth Amendment right to use her own innocent property to pay a reasonable fee for the assistance of counsel. The District Courts order prevents Luis from exercising that right. The Court consequently vacated the judgment of the Court of Appeals and remanded the case for further proceedings.

The United States Supreme Court adds that the constitutional line they have drawn should prove workable. That line distinguishes between a criminal defendants (1) tainted funds and (2) innocent funds needed to pay for counsel. The Court conceded, as Justice Kennedy points out, post, at 12-13, that money is fungible; and sometimes it will be difficult to say whether a particular bank account contains tainted or untainted funds. But the law has tracing rules that help courts implement the kind of distinction they require in this case. For the reasons stated, the United States Supreme Court conclude that the defendant in this case has a Sixth Amendment right to use her own innocent property to pay a reasonable fee for the assistance of counsel. The District Courts order prevents Luis from exercising that right. The Court consequently vacated the judgment of the Court of Appeals and remanded the case for further proceedings.