People v. Myers

2018 NY Slip Op 04685

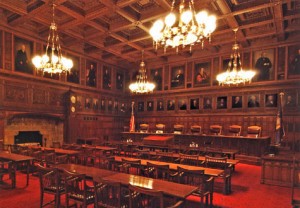

New York Court of Appeals

Decided on June 27, 2018

ISSUE:

Whether the signing of a written instrument in open court in the presence of defense’s counsel, but without an on the record colloquy between the judge and the defendant to waive a defendant’s right to indictment by grand jury is sufficient in demonstrating that a waiver is known, voluntary and intelligent.

HOLDING:

The Court of Appeals held that the signing of a written instrument in open court in the presence of the defendant’s counsel along with the defense counsel’s assurance that he has explained the waiver to the defendant fully satisfies the requirements of the Constitution. The trial court does not need to have an on the record conversation with the defendant in order for the defendant to knowingly and voluntarily waive that Constitutional right.

FACTS OF THE CASE:

Prior to pleading guilty to third-degree burglary, Steven Myers allegedly took the required steps to waive his right to be prosecuted by indictment by a grand jury. The court clerk called Mr. Myers’ case, and his attorney and the prosecutor requested an off-the-record discussion with the court outside the presence of defendant. Mr. Myers was then escorted into the courtroom and discussed the waiver forms with his counsel at the lectern.

The court again called Mr. Myers’ case and announced: “The application for grand jury waiver meets the requirements of the statute so I’m going to sign the order approving the waiver and order the information field.” Mr. Myers’ counsel confirmed receipt of the signed order and waived a reading of the SCI in open court. Immediately, the court recited the plea agreement between Mr. Myers and the prosecution and Mr. Myers allocuted and accepted. As part of the allocution, Mr. Myers waived his Boykin rights, confirmed that he could read and write in English, suffered from no physical, mental or substance related impairment, and had ample time to discuss the case with his attorney.

In his appeal of the judgement of conviction and sentence, Mr. Myers argued that his waiver of indictment was invalid because there was no evidence on record regarding the fact that it was executed in open court and that no explanation by the Trial court as to the waiver of his right to have his case presented to the grand jury. The Appellate Division upheld the validity of the waiver, and Mr. Myers was granted leave to appeal.

COURT’S ANALYSIS:

The Court of Appeals held that the trial court does not have to have a conversation or colloquy with the defendant for the defendant to knowingly and voluntarily waive his right to have his case presented to the Grand Jury. The written waiver along with defense counsel’s assurance that he has explained this waiver to the defendant are sufficient to satisfy the requirements of Art 1 § 6 of NY State Constitution.

Requiring the waiver to be executed in open court in the presence of counsel intentionally allows the opportunity for defendants to consult with counsel before signing the form, which as the records state happened here.

Judge Rivera’s dissent:

“The fact that our Constitution provides for a written waiver as a safeguard against uninformed and invalid waiver does not eliminate a court’s duty to ensure that a defendant understands the contents of the writing and the right being waived.” Rather than including a colloquy as a “better practice; it is critical. No waiver is valid absent sufficient judicial inquiry.” Therefore, Judge Rivera disagreed with the majority that the court could accept Mr. Myers’ written waiver without, at the very least, asking him if he understood what he was signing.

It is said that “Before an individual may be publicly accused of crime and put to the onerous task of defending… from such accusations, the State must convince a Grand Jury composed of the accused’s peers that there exists sufficient evidence and legal reason to believe the accused Guilty” (People v Iannone, 45 NY2d 589, 593-594 [1978]). This principle of a Grand Jury was adapted from English common law in order to aid our citizens in ensuring the ͞sufficiency of a prosecutor’s case” (Pelchat, 62 NY2d at 104) and protect them against excessive prosecutorial power of the State and other agents of the government. Judge Rivera therefore agreed that indictment by Grand Jury should be recognized as “… not merely a personal privilege of the defendant but a public fundamental right, which is the basis of jurisdiction to try and punish an individual…” (People v Boston, 75 NY2d 585, 587 [1990]).

While the majority argues that the drafters of the 1974 amendment sought to establish a ceiling on the procedural defenses of the constitutional right, by requiring the waiver be written, Judge Rivera recognizes that the written document encompasses but one element of ensuring the fulfillment of the Grand Jury indictment waiver be “knowing and voluntary.” (Governor’s Memorandum introducing amendment to art I, § 6, 1973 NY Leg Ann at 6). In fact, the drafters had no reason to even mention that trial courts must orally confirm because by then it was implied that conversation was necessary to ensure the waiver of a constitutional right was knowing and voluntary.