People v Spencer

NY Court of Appeals

NY Court of Appeals

2017 NY Slip Op 05118

Decided on June 22, 2017

Issue: Whether the trial court erred in failing to discharge a sworn juror who, on the fourth day of deliberations, repeatedly stated that she could not separate her emotions from the case and did not have it in her to decide the case on the facts and law.

Holding: The New York Court of Appeals held that, where the juror repeatedly and unambiguously responded that she was unable to render an impartial verdict based solely on the evidence and the law, the trial court erred in failing to discharge the juror as grossly unqualified to serve pursuant to CPL 270.35(1).

Facts: The defendant was indicted for intentionally murdering the victim by stabbing her 38 times. On the fourth day of the jury trial, juror number one inquired about what she needed to do to get excused. The trial judge conducted an extensive inquiry to the juror, and the juror repeatedly stated that she was unable to fulfill her duty because she was incapable of separating her emotions from the facts of the case. The trial judge continuously reiterated to the juror that she needed to separate her emotions and decide only on law and fact and stated that there was no way that the trial could go forward without her. Despite the judges pleas, the jurors stance on her inability to serve as an impartial juror did not change.

Defense counsel moved for a mistrial, arguing that the juror was no longer qualified and there were no available alternate jurors, but the trial court nevertheless instructed the jury to continue to apply the law to the facts without bias and to resume deliberations. The jury eventually reached a verdict that day convicting the defendant of manslaughter in the first degree.

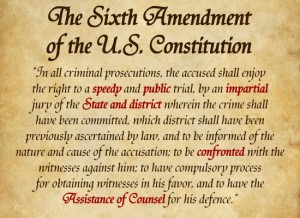

Analysis: As an initial matter, the Court of Appeals recognized that defendants in criminal trials have the constitutional right to an impartial jury. People v. Rodriguez, 71 NY2d 214, 218 (1988). CPL 270.35 protects that right by providing a mechanism for a juror to be dismissed during trial or deliberations.

To determine when a juror becomes disqualified, the Court of Appeals first turned to its conclusion in People v Buford, 69 NY2d 290 (1987), where the Court held that a juror is grossly unqualified only when it becomes obvious that a particular juror possesses a state of mind which would prevent the rendering of an impartial verdict. Buford, 69 NY2d at 298. However, the standard for removal is lower pursuant to CPL 270.20 (1)(b), which provides that a juror may be excused if the juror has a state of mind that is likely to preclude him from rendering an impartial verdict based upon the evidenceġ

In People v Rodriguez, 71 NY2d 214 (1988), the Court of Appeals held that a juror was grossly unqualified where the jurors statements made it clear that she possessed a state of mind which would prevent an impartial verdict. There, the Court did not require a statement of actual bias but, rather, the jurors statements that she could not render the verdict made the juror grossly unqualified. Similarly, although the juror here did not make a statement of actual bias, her continuous statements that she was incapable of rendering an impartial verdict made her unqualified to serve.

Considering the obvious revelations on the record that the juror repeatedly expressed to the judge that she was incapable of separating her emotions from her ability to deliberate and was incapable of fulfilling her duty to reach a verdict based only on the evidence, the Court of Appeals determined that the juror was grossly unqualified to serve. The trial courts attempt to compel the juror to resume deliberations despite her persistent statements that she was unable to do so was erroneous.