Non-Citizen Defendants Entitled to a Jury Trial Under the Sixth Amendment if Deportation is a Consequence of Conviction

People v. Suazo

2018 NY Slip Op 08056

State of New York Court of Appeals

Decided on November 27, 2018

ISSUE:

Whether a noncitizen defendant is entitled to a jury trial under the Sixth where the crime charged is a class B misdemeanor and the defendant may ultimately face deportation as a consequence of the conviction.

HOLDING:

The Court of Appeals held that a non-citizen defendant who is able to demonstrate that a charged crime carries the potential penalty of deportation is entitled to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment because the process of deportation or removal as a penalty is viewed as sufficiently severe under the Court’s interpretation of the Sixth Amendment. The Court of Appeals revered the lower court and ordered a new trial.

FACTS OF THE CASE:

Saylor Suazo was originally charged with a series of class A misdemeanors in local criminal court. Prior to the start of the trial, prosecution moved to reduce the class A misdemeanor charges to attempt crimes, or class B misdemeanors. Unlike class A misdemeanors, the defendant does not have a statutory right to a jury trial.

After the Supreme Court refused to entertain the defense’s argument in opposition to the reduction, defense submitted a written motion asserting the defendant’s right to a jury trial where they reasoned that he was a noncitizen charged with deportable offenses and that the possibility of deportation on a class B misdemeanor was enough to mandate a jury trial pursuant to the Sixth Amendment.

The Supreme Court denied the defendant’s motion and proceeded with a bench trial. Suazo was ultimately found guilty of attempted assault in the third degree, attempted criminal obstruction of breathing or blood circulation, menacing in the third degree and attempted criminal contempt in the second degree. On appeal, the Appellate Division affirmed the judgement and concluded that while deportation is a collateral consequence of conviction, it does not trigger the Sixth Amendment guarantee of a jury trial.

COURT’S ANALYSIS:

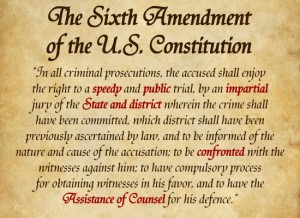

The Courts held that a non-citizen defendant who is able to demonstrate that a charged crime carries the potential penalty of deportation is entitled to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment. The Sixth Amendment states that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed.” In this regard, the court cites Baldwin v New York to explain that the right to a jury trial is intended to ward against oppression by the Government by imposing between the defendant and the accuser a jury of laypeople who are less likely to function or appear as but another arm of the Government.

While the Federal Constitution contains absolute terms, it is clear that not every criminal proceeding warrants a jury trial. Even when the Constitution was first adopted, there were a number of “petty” offenses that were summarily tried without a jury. Therefore, the Courts reason that even though the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in all criminal prosecutions, certain petty offenses can be tried without a jury.

In determining whether an offense is serious or petty, the Courts attempted many different methods in determining whether there was a right to a jury trial. At one time, the Courts analyzed the nature of the offense and whether it was triable by a jury at common law. It eventually became too difficult to make such an assessment because many statutory offenses lacked common-law antecedents. Hence, Courts recently sought objective indications of the seriousness with which society regards the offense. The Supreme Court has since instructed that the most relevant criteria for evaluating seriousness of an offense is the severity of the maximum authorized penalty because in fixing the maximum penalty for a crime, legislature includes within the definition of the crime itself a judgement about the seriousness of the offense and the penalty authorized by the law of the locality may be taken as a gauge of its social and ethical judgements.

The Court looked to Blanton in discussing the term “penalty” and determined that it does not only refer to the maximum prison term but also other penalties that are attached to an offense. Thus, the Court must assess whether the length of the authorized prison sentence term or the seriousness of other punishment is enough in itself to require a jury trial.

To clarify, the emphasis on the maximum authorized prison sentence remains primary but, this heightened focus does not render every other repercussion from a criminal conviction insignificant. As such, the Court must consider additional penalties imposed by law upon conviction and grant a jury trial where elements are so severe that they clearly reflect a legislative determination that the offense in question is a serious one. According to the Supreme Court, this standard, while vague, should ensure the availability of a jury trial in the rare situation where a legislature packs an offense it deems ‘serious’ with onerous penalties that nonetheless do not puncture the six-month incarceration line.

New York’s CPL 340.40 requires that the trial of an information in a local criminal court be a nonjury trial, unless the information charges any misdemeanors. If the information charges any misdemeanors, the defendant must be given a jury trial except when the information which charges a misdemeanor has an authorized term of imprisonment which is not more than six months, in which case there must be a single judge trial. Given that class A misdemeanors carry an authorized maximum penalty of one year in prison, both the Sixth Amendment and CPL 340.40 guarantee a jury trial to all defendants charged with such crimes. Additionally, if prosecuted outside of New York City, defendants facing any misdemeanor charges are entitled to a jury trial pursuant to CPL 340.40. But, defendants in New York City charged with class B misdemeanor crimes or unclassified misdemeanor crimes subject to a maximum term of six months in prison or less are not statutorily entitled to a jury trial.

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) states that a noncitizen may be deported, or forcibly removed from the country, if he or she is convicted of a variety of crimes, including a “crime of moral turpitude” under certain conditions, an “aggravated felony,” most controlled substance offenses, various firearm offenses, “crimes of domestic violence, stalking or violation of a protection of order and crimes against children”. 8USC § 1227 [a] [2] [A] – [F]. There is no argument that, if deemed a penalty for Sixth Amendment purposes, deportation or removal is a penalty of utmost severity. It is a process that typically involves detention by federal immigration authorities, which closely resembles criminal incarceration, amongst other steps that result a greater toll of separation from friends, family, home and livelihood by actual forced removal from the country and sent back to a land which the person may have no significant ties.

The United States Supreme Court has classified deportation as a “drastic measure” emphasizing that deportation is a particularly severe penalty which may be of greater concern to a convicted alien than any potential jail sentence. This is because in many circumstances it amounts to lifelong banishment or exile from the country that one considers home. The Courts have also recently recognized the profound significance of deportation as a consequence of a criminal conviction. They explained that the deportation process deprives the defendant of an exceptional degree of physical liberty by first detaining and then forcibly removing the defendant from the country. Consequently, the defendant may not only lose the blessings of liberty associated with residence in the United States but may also suffer the emotional and financial hardships of separation from work, home and family. Given the severity and inevitability of deportation for many noncitizen defendants, ‘deportation is an integral part—indeed, sometimes the most important part—of the penalty that may be imposed on noncitizen defendants.

While deportation, a federally imposed penalty, is technically a civil collateral consequence of a state conviction, the Court of Appeals explained that deportation is nevertheless intimately related to the criminal process and it is most difficult to divorce the penalty from the conviction in the deportation context because the law has enmeshed criminal convictions and the penalty of deportation for nearly a century and deportation or removal is virtually inevitable for a vast number of noncitizens convicted of crimes. As a result, the Court of Appeals like the Supreme Court acknowledged that deportation cannot be neatly confined to the realm of civil matters unrelated to a defendant’s conviction.