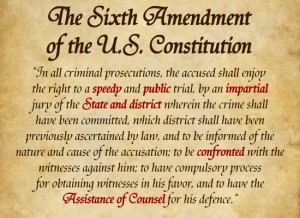

Ineffective Assistance Of Counsel: Fundamental versus Strategic Decisions

People v. Hogan

2016 NY Slip Op 01207

New York Court of Appeals

Decided on: February 19, 2016

Issue: Whether a defendant can claim ineffective assistance of counsel where counsel decided that defendant would not testify before the grand jury without consulting him and failing to timely move to dismiss the indictment for insufficient notice of the grand jury proceeding and whether the drug factory presumption of Penal Law 220.25 was properly considered by the fact finder.

Holding: The Court of Appeals held that while the right to testify before the grand jury is significant and must be scrupulously protected, (People v Brumfield, 24 NY3d 1126, 1128 [2015]); a prospective defendant has no constitutional right to testify before the grand jury, (People v Smith, 87 NY2d 715, 719 [1996]). In contrast to the constitutional nature of the right to testify at trial, the right to testify before the grand jury is a limited statutory right, (CPL 190.50[5]; Smith, 87 NY2d at 719).

Fundamental vs. Strategic Decisions:

It is well established that a defendant, having accepted the assistance of counsel retains authority only over certain fundamental decisions regarding the case, People v. Colon, 90 NY2d 824, 825 [1997]. Fundamental decisions belonging to a defendant are those such as: whether to plead guilty waive a jury trial, testify in his or her own behalf or take an appeal. In contrast, strategic decisions regarding the conduct of trial, which remain in the purview of counsel, include those such as: whether to seek a jury charge on lesser-included offenses (see Colville, 20 NY3d at 32), the selection of particular jurors, and whether to consent to a mistrial. If defense counsel solely defers to a defendant, without exercising his or her own professional judgment, on a decision that is for the attorney, not the accused, to make because it is not fundamental, the defendant is deprived of the expert judgment of counsel to which the Sixth Amendment entitled him or her (Colville, 20 NY3d at 32).

Whether exercising that right is a decision that requires the expert judgment of counsel (Colville, 20 NY3d at 32) because it involves weighing the possibility of a dismissal. Dismissal, may be remote against the potential disadvantages of providing the prosecution with discovery and impeachment material damaging admissions, and prematurely narrowing the scope of possible defenses (People v Brown, 116 AD3d 568, 569 [1st Dept 2014]. The various risks and benefits that must be considered render the decision of whether to exercise this statutory right an appropriate one for the lawyer, not the client (Ferguson, 67 NY2d at 309). Failure to facilitate Defendants testimony before the grand jury is not denial of effective assistance of counsel.

Whether exercising that right is a decision that requires the expert judgment of counsel (Colville, 20 NY3d at 32) because it involves weighing the possibility of a dismissal. Dismissal, may be remote against the potential disadvantages of providing the prosecution with discovery and impeachment material damaging admissions, and prematurely narrowing the scope of possible defenses (People v Brown, 116 AD3d 568, 569 [1st Dept 2014]. The various risks and benefits that must be considered render the decision of whether to exercise this statutory right an appropriate one for the lawyer, not the client (Ferguson, 67 NY2d at 309). Failure to facilitate Defendants testimony before the grand jury is not denial of effective assistance of counsel.

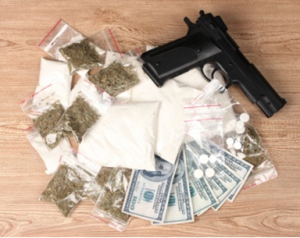

The Court also held that the fact finder properly considered the drug factory presumption rule contained in Penal Law 220.25, which states: the presence of a narcotic drug in open view in a room, other than a public place, under circumstances evincing intent to unlawfully mix, compound, package or otherwise prepare for sale such controlled substance is presumptive evidence of knowing possession thereof by each and every person in close proximity to such controlled substance at the time such controlled substance was found.

Facts: Defendant was arrested on felony drug possession charges after police executing a search warrant at his former girlfriends apartment observed him running to the bathroom from the kitchen, where packaged and loose cocaine, baggies, and a razor blade were found in open view. Before a long holiday weekend, the People sent notice to defense counsel, by fax, indicating that the case would be presented to a grand jury on the next business day. Defense counsel had already left the office and did not receive notice until the morning. He then contacted the district attorneys office and indicated that he would not have defendant testify because he didnt see the benefit, only the harm. It is undisputed that counsel did not speak with defendant about testifying before the grand jury, which ultimately voted to indict defendant, charging him with, criminal possession of a controlled substance in the third and fifth degrees.

Defendant moved to dismiss the indictment on the ground that he was denied an opportunity to testify before the grand jury due to insufficient notice. Supreme Court denied the motion as untimely. At the ensuing non-jury trial, police testified that, upon entering the apartment, they saw the loose cocaine, baggies, and a razor blade in plain view. Defendants former girlfriend also testified that she had purchased the cocaine and was in the process of moving it and Defendant was convicted and was sentenced as a second felony offender, to an aggregate term of nine years in prison. Defendant appealed the Appellate Division.

Defendant moved to dismiss the indictment on the ground that he was denied an opportunity to testify before the grand jury due to insufficient notice. Supreme Court denied the motion as untimely. At the ensuing non-jury trial, police testified that, upon entering the apartment, they saw the loose cocaine, baggies, and a razor blade in plain view. Defendants former girlfriend also testified that she had purchased the cocaine and was in the process of moving it and Defendant was convicted and was sentenced as a second felony offender, to an aggregate term of nine years in prison. Defendant appealed the Appellate Division.

Legal Analysis: Defendant argues that his counsel had no authority to decide whether he would testify before the grand jury because that choice is fundamental and, therefore, reserved exclusively for defendants. The Court of Appeals has stated that it is well established that a defendant, having accepted the assistance of counsel retains authority only over certain fundamental decisions regarding the case, (People v Colon, 90 NY2d 824, 825 [1997]).

Fundamental decisions belonging to a defendant are those such as whether to plead guilty, waive a jury trial, testify in his or her own behalf or take an appeal. In contrast, strategic decisions regarding the conduct of trial, which remain in the purview of counsel, include those such as whether to seek a jury charge on lesser-included offenses, the selection of particular jurors, and whether to consent to a mistrial. If defense counsel solely defers a defendant, without exercising his or her professional judgment, on a decision that is for the attorney, not the accused, to make because it is not fundamental, the defendant is deprived of the expert judgment of counsel to which the Sixth Amendment entitles him or her (Colville, 20 NY3d at 32).

The Court addressed a defendant advancing an ineffective assistance claim must demonstrate the absence of strategic or other legitimate explanations for counsels alleged shortcomings, (People v Benevento 91 NY2d 708, 712 [1998]), and defendant cannot do so here because counsel stated his thinking in plain language on the record, (People v Nesbitt, 20 NY3d 1080, 1082 [2013[) regarding why, as a matter of strategy, he decided that defendant would not testify before the grand jury. Accordingly, the Court affirmed the Appellate Divisions order.

Drug Factory Presumption Rule:

The presence of a narcotic drug in open view in a room, other than a public place, under circumstances evincing an intent to unlawfully mix, compound, package or otherwise prepare for sale such controlled substance is presumptive evidence of knowing possession thereof by each and every person in close proximity to such controlled substance at the time such controlled substance was found.

The Court also stated that the provision in People v. Kims, explaining that the statute allows the court to charge the fact-finder with permissible presumption, under which the fact-finder may assume the requisite criminal possession simply because the defendant while not in actual physical possession, is within a proximate degree of closeness to drugs found in plain view, under circumstances that evince the existence of a drug sale operation (24 NY3d 422, 432 [2014[).

Under the circumstances here, the court properly granted the Peoples request that it consider the presumption. Defendants former girlfriend admitted that the bagged crack, loose cocaine and baggies were in plain view and that she was in the process of moving the cocaine that she was probably going to sell. The police further testified that defendant was in close proximity to the cocaine and that the drugs, baggies and razor blade were in open view. The evidence in plain view was sufficient to establish that drugs were being packaged or otherwise prepared for sale in the apartment, permitting the conclusion that defendant who was in close proximity to the drugs, knowingly possessed them, Penal Law 220.25[2]. The Court of Appeals, affirmed the order of the Appellate Division.