Unconstitutional Stops And The Attenuation Doctrine

The United States Supreme Court

Utah v Strieff

No. 14-1373

Decided: June 20, 2016

Issue: Whether the attenuation doctrine applies when an officer makes an unconstitutional investigatory stop, learns during that stop that the suspect is subject to a valid arrest warrant, and proceeds to arrest the suspect and seize incriminating evidence during a search incident to that arrest?

Holding: The United States Supreme Court held that the evidence the officer seized as part of the search incident to arrest was admissible because the officer’s discovery of the arrest warrant attenuated the connection between the unlawful stop and the evidence seized incident to arr est.

est.

Facts: In this case, petitioner Strieff was arrested pursuant to information from a police dispatcher, who reported that Strieff had an outstanding warrant for a traffic violation. First, the court considered the presence of a valid arrest warrant to be an extraordinary intervening circumstance, App. to Pet. for Cert. 102, United States v. Simpson, 439 F. 3d 490, 496 (CA8 2006).

Second, the court stressed the absence of flagrant misconduct by Officer Fackrell, who was conducting a legitimate investigation of a suspected drug house. Strieff conditionally pleaded guilty to reduced charges of attempted possession of a controlled substance and possession of drug paraphernalia, but reserved his right to appeal the trial courts denial of the suppression motion.

The Utah Court of Appeals affirmed. 2012 UT App 245, 286 P. 3d 317 and the Utah Supreme Court reversed. 2015 UT 2, 357 P. 3d 532, holding that the evidence was inadmissible because only a voluntary act of a defendant’s free will (as in a confession or consent to search) sufficiently breaks the connection between an illegal search and the discovery of evidence. Id., at 536. Because Officer Fackrell’s discovery of a valid arrest warrant did not fit this description, the court ordered the evidence suppressed.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve disagreement about how the attenuation doctrine applies where an unconstitutional detention leads to the discovery of a valid arrest warrant, 576 U.S. __(2015) and reversed.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve disagreement about how the attenuation doctrine applies where an unconstitutional detention leads to the discovery of a valid arrest warrant, 576 U.S. __(2015) and reversed.

Legal Analysis: The United States Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment protects the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures. Because officers who violated the Fourth Amendment were traditionally considered trespassers, individuals subject to unconstitutional searches or seizures historically enforced their rights through tort suits or self-help, Davies, Recovering the Original Fourth Amendment, 98 Mich. L. Rev. 547, 625 (1999).

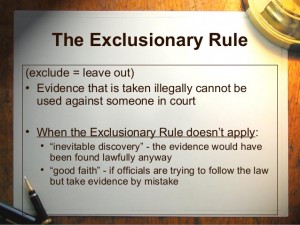

In the 20th century, however, the exclusionary rule that often requires trial courts to exclude unlawfully seized evidence in a criminal trial became the principal judicial remedy to deter Fourth Amendment violations. See, e.g., Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643, 655 (1961).

The Exclusionary Rule often requires trial courts to exclude unlawfully seized evidence in a criminal trial and became the principal judicial remedy to deter Fourth Amendment violations, Mapp v Ohio 367 U.S. 643, 655. Under the Courts precedents, the exclusionary rule encompasses both the primary evidence obtained as a direct result of an illegal search or seizure and, relevant here, evidence later discovered and found to be derivative of an illegality, the so-called fruit of the poisonous tree. Segura v. United States, 468 U. S. 796, 804 (1984). The Court held that there are several exceptions to the rule. Three of these exceptions involve the casual relationship between the unconstitutional act and the discovery of evidence.

Exceptions to the Exclusionary Rule

Exceptions to the Exclusionary Rule

First, the independent source doctrine allows trial courts to admit evidence obtained in an unlawful search if officers independently acquired it from a separate, independent source. See Murray v. United States, 487 U. S. 533, 537 (1988).

Second, the inevitable discovery doctrine allows for the admission of evidence that would have been discovered even without the unconstitutional source. See Nix v. Williams, 467 U. S. 431, 443 444 (1984).

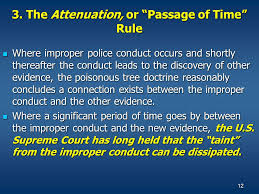

Third, and at issue here, is the attenuation doctrine: which holds, evidence is admissible when the connection between unconstitutional police conduct and the evidence is remote or has been interrupted by some intervening circumstance, so that the interest protected by the constitutional guarantee that has been violated would not be served by suppression of the evidence obtained. Hudson, supra, at 593.

Attenuation Doctrine

Turning to the application of the attenuation doctrine to this case, the Court held that they must first address a threshold question: whether this doctrine applies at all to a case like this, where the intervening circumstance that the State relies on is the discovery of a valid, pre-existing, and untainted arrest warrant. The Utah Supreme Court declined to apply the attenuation doctrine because it read our precedents as applying the doctrine only to circumstances involving an independent act of a defendant’s free will in confessing to a crime or consenting to a search. 357 P. 3d, at 544.

The attenuatio n doctrine evaluates the causal link between the government’s unlawful act and the discovery of evidence, which often has nothing to do with a defendants actions. And the logic of this Court’s prior attenuation cases is not limited to independent acts by the defendant. It remains for this Court to address whether the discovery of a valid arrest warrant was a sufficient intervening event to break the causal chain between the unlawful stop and the discovery of drug-related evidence on Strieff’s person.

n doctrine evaluates the causal link between the government’s unlawful act and the discovery of evidence, which often has nothing to do with a defendants actions. And the logic of this Court’s prior attenuation cases is not limited to independent acts by the defendant. It remains for this Court to address whether the discovery of a valid arrest warrant was a sufficient intervening event to break the causal chain between the unlawful stop and the discovery of drug-related evidence on Strieff’s person.

The three factors articulated in Brown v. Illinois, 422 U. S. 590 (1975), guide the Courts analysis.

First, the court looks to the temporal proximity between the unconstitutional conduct and the discovery of evidence to determine how closely the discovery of evidence followed the unconstitutional search. Id., at 603.

Second, it considers the presence of intervening circumstances. Id., at 603, 604. Third, and particularly significant, the Court held that they examine the purpose and flagrancy of the official misconduct. Id., at 604.

The Court held that the existence of a valid warrant favors finding that connection between unlawful conduct and the discovery of evidence is sufficiently attenuated to dissipate the taint. In this case, the warrant was valid, it predated Officer Fackrell’s investigation and it was entirely unconnected with the stop. One Officer Fackrell discovered the warrant, he had an obligation to arrest Strieff. A warrant is a judicial mandate to an officer to conduct a search or make an arrest, and the officer has a sworn duty to carry out its provisions. United States v. Leon, 468 U. S. 897, 920, n. 21 (1984).

Officer Fackrell’s arrest of Strieff thus was a ministerial act that was independently compelled by the pre-existing warrant. And once Officer Fackrell was authorized to arrest Strieff, it was undisputedly lawful to search him as incident to his arrest to protect Officer Fackrell’s safety. The Court held that these errors in judgment hardly rise to a purposeful or flagrant violation of Strief’s Fourth Amendment rights. While Officer Fackrell’s decision to initiate the stop was mistaken, his conduct was therefore, lawful.

Officer Fackrell saw Strieff leave a suspected drug house. And his suspicion about the house was based on an anonymous tip and his personal observations. Applying these factors, we hold that the evidence discovered on Strieff’s person was admissible because the unlawful stop was s ufficiently attenuated by the preexisting arrest warrant. Although the illegal stop was close in time to Strieff’s arrest, that consideration is outweighed by two factors supporting the State. The outstanding arrest warrant for Strieff’s arrest is a critical intervening circumstance that is wholly independent of the illegal stop. The discovery of that warrant broke the causal chain between the unconstitutional stop and the discovery of evidence by compelling Officer Fackrell to arrest Strieff. And, it is especially significant that there is no evidence that Officer Fackrell’s illegal stop reflected flagrantly unlawful police misconduct.

ufficiently attenuated by the preexisting arrest warrant. Although the illegal stop was close in time to Strieff’s arrest, that consideration is outweighed by two factors supporting the State. The outstanding arrest warrant for Strieff’s arrest is a critical intervening circumstance that is wholly independent of the illegal stop. The discovery of that warrant broke the causal chain between the unconstitutional stop and the discovery of evidence by compelling Officer Fackrell to arrest Strieff. And, it is especially significant that there is no evidence that Officer Fackrell’s illegal stop reflected flagrantly unlawful police misconduct.

The United States Supreme Court held that the evidence Officer Fackrell seized as part of his search incident to arrest is admissible because his discovery of the arrest warrant attenuated the connection between the unlawful stop and the evidence seized from Strieff incident to arrest. The judgment of the Utah Supreme Court, accordingly, is reversed.