Fifth Amendment Right To Remain Silent: Delay In Arraignment And Knowing Waivers

People v. Jin Cheng Lin

2016 NY Slip Op 01205

New York Court of Appeals

Decided on: February 18, 2016

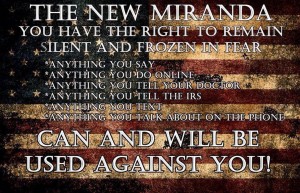

Issue: Whether Defendants confession was an involuntary product of psychological pressure during his lengthy detention and the prearraignment delay following his arrest and whether he knowingly waived his Miranda rights because of his inability to speak English.

Holding: The Court of the Appeals held that it is the Peoples burden (People v Holland, 48 NY2d 861, 862 [1979]), to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the statements of a defendant they intend to rely upon at trial are voluntary, (People v Thomas, 22 NY3d 629, 641 [2014]). In order to assess the voluntariness of defendants statements, a court must consider the totality of the circumstances. A series of circumstances may be insufficient to deem a confession involuntary.?While defendant makes a compelling case that the police were intentionally dilatory in delaying his arraignment and thus prolonged his detention, the Court held that they cannot say, based on the totality of the circumstances and as a matter of law, that his statements were involuntary.

The Court held that a defendants waiver of his Miranda rights must be knowing, voluntary, and intelligent (Miranda v Arizona, 384 US 436, 444 [1966]). The People must establish that the defendant grasped that he or she did not have to speak to the interrogator; that any statement might be used to the subjects disadvantage; and that an attorneys assistance would be provided upon request, at any time, and before questioning is continued.

The Court held that a defendants waiver of his Miranda rights must be knowing, voluntary, and intelligent (Miranda v Arizona, 384 US 436, 444 [1966]). The People must establish that the defendant grasped that he or she did not have to speak to the interrogator; that any statement might be used to the subjects disadvantage; and that an attorneys assistance would be provided upon request, at any time, and before questioning is continued.

Facts: Defendant Jin Cheng Lin challenges his conviction for murder, burglary and attempted robbery arising from events leading to the death of Cho Man Ng and her brother, Sek Man Ng. Defendant was not a suspect in the murders, but during the course of police investigation, detectives grew suspicious of his role in the crimes after they identified several inconsistencies in his statements to police. After several hours of questioning over three days, and after having implicated two others in the crimes, he confessed to brutally killing Cho and Sek.

Defendant was charged with six counts of Murder in the First degree, six counts of Murder in the Second Degree, one count of Assault in the First Degree, three counts of Burglary in the first degree, three counts of Attempted Robbery in the First Degree, and Criminal Possession of a Weapon in the Fourth Degree.

Defendant moves to suppress his statements to the police. At the suppression hearing, the People submitted testimony from detectives describing the investigation, as well as documentary evidence that defendant was sufficiently fluent in English to understand the surrounding events and his constitutional rights. Defendant wrote out statements in English then signed them. Defendant spoke to Detectives in both English and Cantonese. The court denied defendants motion to suppress, concluding that his statements were voluntary. ?At trial, several of the officers repeated their testimony from the suppression hearing. All of defendants written statements, including his confession were admitted into evidence. The Appellate Division vacated his convictions and sentences on the second degree murder counts and granted leave to appeal to the Court of Appeals.

On Appeal, defendant asserts that the judgment should be reversed and a new trial ordered on the grounds that the People failed to establish that his statements to the police were voluntary and that he knowingly and intelligently waived his Miranda rights. The Court of Appeals held that there is support in the record for the lower courts determination that defendant understood his Miranda rights and affirmed the order of the Appellate Division.

Legal Analysis: Defendant argues that the voluntariness of his statements must be considered in light of the confinement conditions he was exposed to during his lengthy detention and the unjustified prearraingment delay of 28 hours following his arrest. The Court of Appeals has stated that an undue delay in arraignment should properly be considered in assessing the voluntariness of a defendants confession, (People v Ramos, 99 NY2d 27, 35 [2002]), and may serve as a significant reason why a defendants confession could not be considered voluntary.

CPL 140.20 provides, in relevant part that upon arresting a person without a warrant, a police officer, after performing without unnecessary delay all recording, fingerprinting and other preliminary police duties requires in the particular case, must, without unnecessary delay bring the arrested person or cause him to be brought before a local criminal court and file therewith an appropriate accusatory instrument charging him with the offense or offenses in question. CPL 140.20(1) requires that a prearraignment detention not be prolonged beyond a time reasonably necessary to accomplish the tasks required to bring an arrestee to arraignment. The absence of similar language in CPL 140.20(1) suggests that an investigation cannot serve as an automatic excuse for open-ended questioning solely intended to undermine the very rights protected by the statute. A per se rule that a delay associated with an investigation can never be unnecessary, regardless of the circumstances, would undermine the salutary goals of CPL 140.20(1).

To be clear, the overriding concern is not with the mere fact that a delay has transpired, but rather with the effect of an unnecessary time lag between arrest and arraignment on a defendants ability to decide whether to speak and how to respond to questioning. Thus, while unwarranted prearriagnment delay is a special circumstance. The Court has acknowledged that, except in cases of involuntariness, a delay in arraignment, even if prompted by a desire for further police questioning, does not warrant suppression.

A court must give careful consideration to a delay that impacts a defendants resistance by extending exposure to the pressures of interrogation to the point where a defendants will bends to the desires of the interrogators, or during which a defendant is led to believe that the only way to end interrogation is by bargaining away legal rights. Here, Defendant was not subjected to the type of deprivations and psychological pressure described in People v Holland 48 NY2d at 863. Defendant was able to eat, drink, and take bathroom breaks. He was even allowed to smoke cigarettes.

Additionally, there is not enough evidence to show that the interrogation was unlawful because of Defendants lack of understanding in English. There was evidence of his school attendance in the United States and that he had completed the 11th grade. The People presented evidence to establish his understanding of the English language and the understanding of his rights. Detectives advised Defendant of his Miranda rights in both English and Cantonese and Defendant wrote the word yes next to each right and signed the form.