Federal RICO Indictment Alleges Money Laundering In Orange County, California Bank

Last Thursday, the Department of Justice announced that sixteen individuals had been named in a racketeering indictment filed in federal court. Allegedly, the head of Saigon National Bank, located in Westminster, California, was involved in money laundering schemes. Four other defendants were also arrested last week in connection with the money laundering schemes and were named in separate indictments.

Federal Crimes In California

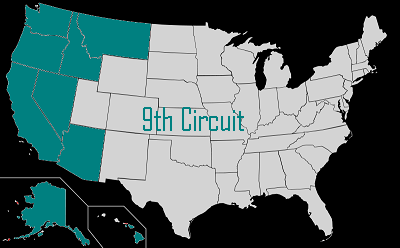

In the main indictment, six individuals were charged in the U.S. District Court of Central California with violating the federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) by laundering drug money through a business they either worked at or managed. The defendant facing the most serious charges is Tu Chau Lu of Fullerton, California. Lu was the president and CEO of Saigon National Bank from 2009-2015.

According to the Department of Justice, Lu and five other individuals were members of an international criminal organization that dealt drugs and laundered money in countries beyond the U.S., including China, Cambodia, Mexico and Switzerland.

Allegedly, Lu used his senior position at Saigon National Bank along with his network of connections to launder money for members of the drug organization. Other members of the organization allegedly engaged in other money laundering schemes, but the indictment states that all of the defendants worked with Lu, or under him.

In one of the described incidents, an undercover officer delivered cash to Lu and other defendants. The officer allegedly told the defendants that the money was from drug deals. Despite knowing the money had been obtained illegally, Lu and the other defendants allegedly helped the undercover informer convert the cash into cashiers checks made out to a company that the informer allegedly owned.

Each racketeering charge carries a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison. This sentence is in addition to any associated with the underlying criminal charges (in this case, namely money laundering).

Federal Criminal Law In California

Under the federal RICO statute, it is illegal for any person employed by or associated with any enterprise… to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprises affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity.

The Supreme Court has held that in order for an individual to be convicted under this law the government must prove: (1) conduct (2) of an enterprise (3) through a pattern, (4) of racketeering activity. ?Racketeering activity includes many criminal offenses that are listed as predicate acts in the statute. These predicate acts range from serious offenses like murder, to lesser offenses like mail fraud.

Generally, the government will spend significant time gathering evidence to ensure that those charged have engaged in multiple acts of racketeering . Regardless, only two need to be proved in order to constitute a pattern under the statute. A defendant charged under Rico must also have some part in directing the businesss affairs.

In other words, an individual cannot be liable under RICO unless they have participated in the operation of the business, as an employee or manager. If an individual has simply performed work for a business, for example as an outside hired contractor, he is not necessarily directing the businesss affairs. This could explain why certain individuals charged in the indictment were not included in the RICO charge and were instead only charged with conspiracy or money laundering.

Finally, the government will need to prove that all the defendants actually knew about the illegal nature of their actions, and were not simply blindly following their CEOs orders.

Appealing The Verdict

It remains to be seen if all or any of the defendants will be convicted in this case. The government must prove the racketeering beyond a reasonable doubt. While the allegations may be easily proved against Lu, the extent of the involvement of the other defendants is not as clear.

Furthermore, the government may need to rely on the testimony of the undercover informant extensively. Relying so much on one witness could make it more difficult for them to prove racketeering.

In a recent federal case in New York, Vincent Asaro, a well-known mobster, was found not guilty of racketeering. In that instance, the government relied heavily on the testimony of an informer. Asaros attorney repeatedly attacked the informers credibility during her closing arguments, saying that he was an experienced liar. After two days of deliberations, the jury found Asaro not guilty on all counts.