Constitutional Violation Under Batson v Kentucky: Striking Of Two Black Prospective Jurors Was Racially Motivated

United States Supreme Court

Foster v Chatman

No. 14-8349

Decided: May 23, 2016

Issue: Whether the striking of two black prospective jurors was racially motivating violating petitioner’s Constitutional rights under?Batson v Kentucky, 474 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d.69.

Holding: The United States Supreme Court has held that the Prosecution violated Batson when it used peremptory strikes to exclude black prospective juror’s violating Batson.

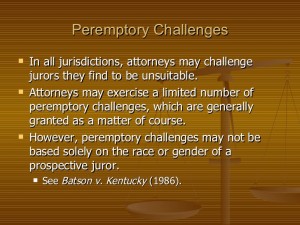

Batson has a three -step process for adjudicating claims such as Foster’s.

First: a defendant must make a prima facie showing that a peremptory challenge has been exercised on the basis of race; second, if that showing has been made, the prosecution must offer a race-neutral basis for striking the juror in question; and third, in light of the parties submissions, the trial court must determine whether the defendant has shown purposeful determination, Snyder v Louisiana, 552 U.S. 472, 477, 128 S.Ct. 1203, 170 L.ED.2d 175.

Facts: Petitioner Timothy Foster was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death in a Georgia court. During jury selection at trial, the State exercised peremptory strikes against all four black prospective jurors qualified to serve. Foster argued that the States use of those strikes was racially motivated in violation of Batson v Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986). The trial court and the Georgia Supreme Court rejected Fosters Batson claim.

Foster then sought a writ of habeas corpus from the Superior Court; that court denied relief and declined to issue the Certificate of Probable cause necessary under Georgia law for Foster to pursue an appeal. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari where they reversed and remanded.

Legal Analysis: The United States Supreme Court held that before turning to the merits of Fosters Batson claim, they address a threshold issue. Neither party contests the Courts jurisdiction to review Fosters claims, but the Court held that they have an independent obligation to determine whether subject-matter jurisdiction exists, even in the absence of a challenge from any party, Arbaugh v Y & H Corp., 546 U.S. 500, 514, 126 S.Ct. 1235, 163 L.Ed.2d 1097 (2006).

The United States Supreme Court held that they lack jurisdiction to entertain federal claim on review of a state court judgment if that judgment rests on a state law ground that is both independent of the merits of the federal claim and an adequate basis for the Courts decision, Harris v Reed, 489 U.S. 255, 260, 109 S.Ct 1038, 103 L.Ed.2d 308 (1989).

The state habeas court noted that Fosters Batson claim was not reviewable based on the doctrine of res judicata under Georgia Law App. 175. The Georgia Supreme Courts unelaborated order on review provides no reasoning for its decision. That raises the question whether the Georgia Supreme Courts order-the judgment from which Foster sought certiorari?rests on adequate and independent state law ground so as to preclude the Courts jurisdiction over Fosters federal claim. The United States Supreme Court concluded that it does not.

The state habeas court noted that Fosters Batson claim was not reviewable based on the doctrine of res judicata under Georgia Law App. 175. The Georgia Supreme Courts unelaborated order on review provides no reasoning for its decision. That raises the question whether the Georgia Supreme Courts order-the judgment from which Foster sought certiorari?rests on adequate and independent state law ground so as to preclude the Courts jurisdiction over Fosters federal claim. The United States Supreme Court concluded that it does not.

When application of a state law bar depends on a federal constitutional ruling, the state-law prong of the courts holding is not independent of federal law, and the Court held that its jurisdiction is not precluded, Ake v Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 75, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 85 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985); Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold Reservation v Wold Engineering, P.C., 467 U.S. 138, 152, 104 S.Ct. 2267, 81 L.Ed.2d 113 (1984).

The United States Supreme Court held that Georgia Supreme Court argued that Fosters Batson claim is not reviewable due to the doctrine of res judicata. However, because Foster claims that additional evidence allegedly supporting this ground was discovered subsequent to the Georgia Supreme Courts ruling, [on direct appeal], the United States Supreme Court held that they will review the Batson claims to whether Foster has shown any change in the facts sufficient to overcome the res judicata bar. The Court held that it is apparent that the state habeas courts application of res judicata to Fosters Batson claim was not independent of the merits of his federal constitutional challenge. That court’s invocation of res judicata, therefore, poses no impediment to The United States Supreme Courts review of Fosters Batson claim, Ake, 470 U.S., at 75. The Constitution forbids striking even a single prospective juror for a discriminatory purpose, Snyder v Louisiana, 552, U.S. 472, 478, 128 S.Ct. 1203, 170 L.Ed.2d 175 (2008).

In Batson v Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 provides a three-step process to determine when a strike is discriminatory:

First, a defendant must make prima facie showing that a peremptory challenge has been exercised on the basis of race; ; second, if that showing has been made, the prosecution must offer a race-neutral basis for striking the juror in question; and third, in light of the parties submissions, the trial court must determine whether the defendant has shown purposeful determination, Snyder, 552, U.S., at 476-47.

Both parties agree that Foster has demonstrated a prima facie case and that the prosecutors have offered race-neutral reasons for their strikes. The United States Supreme Court, therefore, address only Batson’s third step. That step turns on factual determinations, and, in the absence of exceptional circumstances, the Court held that it defers to the state court for factual findings unless it concludes that they are clearly erroneous, Snyder, 552 U.S., at 477.

The United States Supreme Court held that they have made it clear that in considering a Batson objection, or in reviewing a ruling claimed to be a Batson error, all of the circumstances that bear upon the issue of racial animosity must be consulted, Snyder, 552 U.S., at 478.

Here, Foster centers his Batson claim on the strikes of two black prospective jurors. On the Prosecutions face, Lanier’s justification for the strike seems reasonable enough. The United States Supreme Court held that the independent examination of the record, however, reveals that much of the reasoning provided by Lanier has no grounding in fact. The first five names on the definite “NO’s” list were all black. Lanier claimed that he struck Garrett because she was too young, and the State was looking for older jurors that would not easily identify with the defendant. Yet, Garrett was 34, and the State declined to strike eight white prospective jurors under the age of 36. Two of those white jurors served on the jury; one of those two was only 21 years old. In sum, the United States Supreme Court held that in evaluating the strike of Garrett, they are not faced with a single isolated misrepresentation.

In Miller-El v Dretke, if a prosecutor’s proffered reason for striking a black panelist applies just as well to an otherwise-similar nonblack (panelist) who is permitted to serve, that is evidence tending to prove purposeful discrimination, 545 U.S. 231, 241, 125 S.Ct. 2317, 162 L.Ed.2d 196 (2005). With respect to both jurors, such evidence is compelling. But that is not all. There are also the shifting explanations, the misrepresentations of the record, and the persistent focus on race in the prosecution’s file. Considering all of the circumstantial evidence that bears upon the issue of racial animosity, the United States Supreme Court held that they are left with the firm conviction that the strikes of the two jurors were a motivated and substantial part by discriminatory intent. The order of the Georgia Supreme Court is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings.